The Sacrament of the Last Supper, Dali 1955

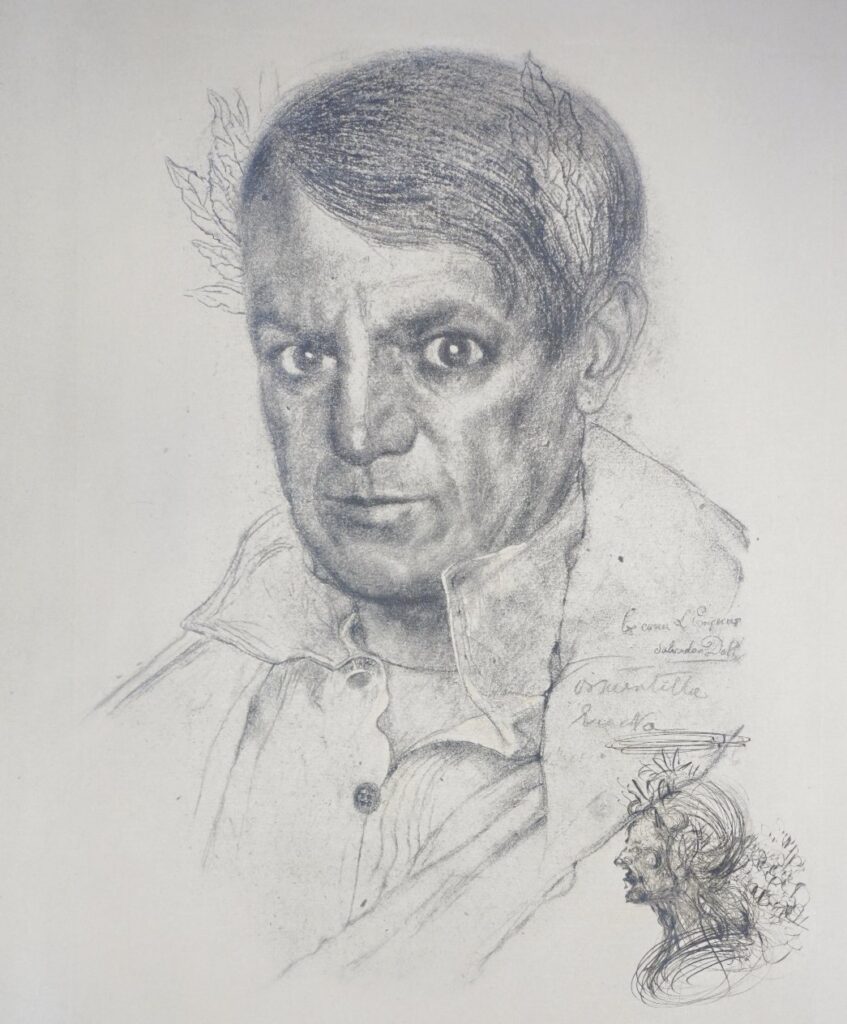

Dali’s Portrait of Picasso

When it comes to 20th-century art, few names shine as brightly—or as enigmatically—as Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí. Both were Spanish. Both were revolutionary. Both reshaped the visual language of modern art in profound and lasting ways. But their relationship was far from simple. It was a swirling mix of admiration, rivalry, ideological tension, and aesthetic contrast—a dialogue that both connected and divided them.

Early Admiration: Dalí’s First Meeting with Picasso

Dalí’s fascination with Picasso began early. In 1926, the young, ambitious Dalí traveled to Paris, eager to meet the great modernist. He brought with him a collection of drawings as a kind of visual homage. Picasso, then at the height of his fame, received the young surrealist politely but cautiously.

Dalí would later say:

“Picasso is Spanish, I am Spanish. Picasso is a genius, I am a genius. Picasso is famous, I am famous… Picasso is old, I am young. Picasso is right, I am right.”

This mix of reverence and ego beautifully encapsulates the complex tone of their relationship: admiration with a side of rivalry.

The Early Influence: Cubism and Beyond

Dalí’s early work, especially in the 1920s, was clearly influenced by Picasso’s Cubist innovations. The older artist’s ability to dismantle and reassemble reality encouraged Dalí to rethink the constraints of traditional form. Picasso gave Dalí and his generation permission to rebel—to explore the irrational, the mythological, and the subconscious.

While Dalí would soon drift into the realm of Surrealism, the foundations laid by Picasso’s visual deconstruction of space and form were instrumental in shaping his early visual imagination.

Diverging Paths: Cubism vs. Surrealism

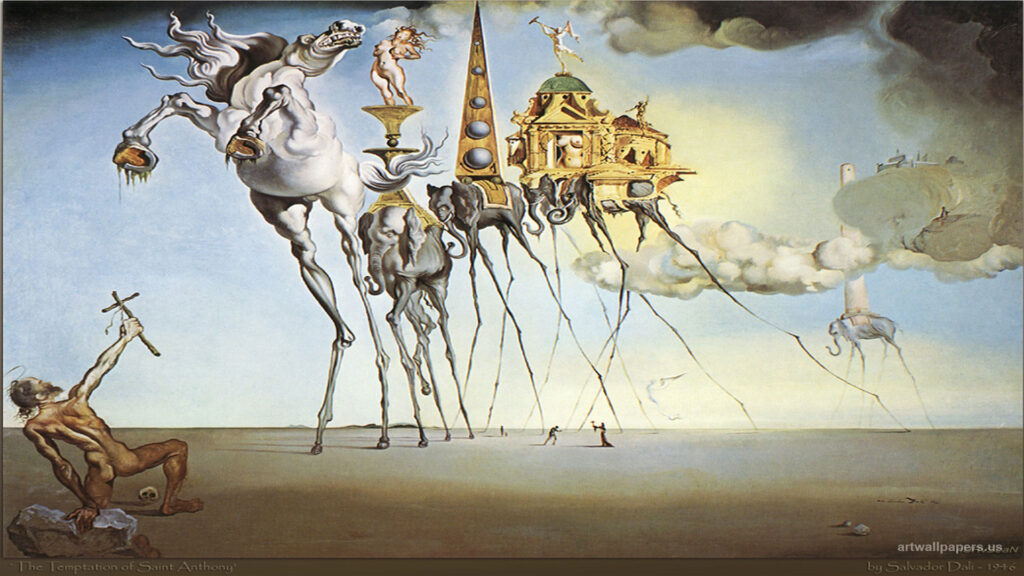

Though Picasso flirted with Surrealist themes in works like Minotauromachy and Guernica, he never officially joined the Surrealist movement. Dalí, on the other hand, became Surrealism’s flamboyant poster child, developing his paranoiac-critical method and painting dreamscapes that blurred the boundaries between illusion and reality.

Despite their stylistic divergence, both artists were obsessed with myth, sexuality, dreams, and inner psychology—themes they expressed through radically different visual languages.

Politics and Conflict: Picasso’s Protest vs. Dalí’s Silence

Perhaps the most dramatic break between the two came during the Spanish Civil War and WWII. Picasso, who aligned himself with anti-fascist causes, created the monumental Guernica as a condemnation of Franco’s brutality. Dalí, however, avoided political engagement and later expressed ambiguous or even sympathetic views toward Franco’s regime.

Picasso, who saw art as a weapon of resistance, viewed Dalí’s stance as morally bankrupt, and their relationship grew increasingly distant.

Homage and Legacy: Dalí’s Surreal Tribute to Picasso

Despite their ideological and stylistic differences, Dalí never stopped admiring Picasso. In 1972, just two years before Picasso’s death, Dalí painted Portrait of Picasso in the Twenty-First Century—a grotesque, fantastical tribute that both mocked and revered the master.

Dalí said:

“He is a genius; he is a destructive genius; he is a genius who never erred.”

For all their differences, Dalí recognized that Picasso had changed art forever—a force of creation and destruction unlike any other.

Conclusion: Two Sides of Modern Genius

Picasso and Dalí were like opposite poles of a powerful magnetic field. Picasso was the analytical modernist, deconstructing form and rebuilding it with raw intensity. Dalí was the dreamer-mystic, pulling the unconscious into the spotlight with razor-sharp realism and theatrical flair.

Their relationship was never warm, never close—but it was always electric. In each other, they found not a friend, but a challenge—a mirror of possibility, a counterforce pushing them further into their own unique artistic frontiers.

Together, they shaped what art could be in the 20th century and beyond.