Warhol once remarked: “Picasso did everything — and I’m doing everything he didn’t do. I’m using industrial techniques, he used craft. I’m not painting by hand — I’m printing. But I’m still doing what he did — which is everything.” This comment reveals not rejection, but deep homage through inversion — Warhol working in Picasso’s wake, responding in kind.

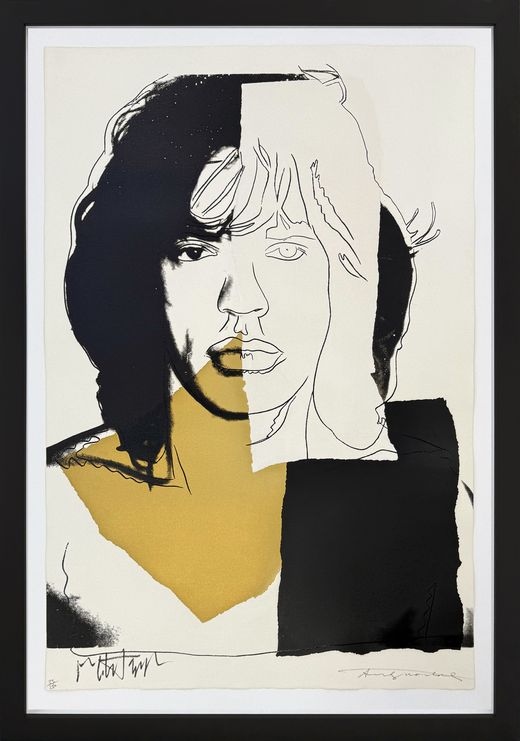

Note: Featured Image is by Warhol, a silkscreen of a Picasso painting.

At first glance, Pablo Picasso and Andy Warhol might seem like artistic opposites. Picasso — the passionate, painterly modernist — and Warhol — the cool, detached postmodernist. Yet beneath their surface differences lies a profound and surprising connection: Warhol was deeply influenced by Picasso, not only in terms of style but more importantly in terms of artistic philosophy, innovation, and persona. Picasso’s shadow looms large over Warhol’s career — as a benchmark, a rival, and a model for what it means to be an artist in the modern age.

1. Picasso as the Prototype of the Modern Celebrity Artist

Long before Warhol coined the phrase “famous for fifteen minutes,” Picasso had already redefined the artist as a global celebrity. Warhol, who came of age in an era dominated by mass media and consumer culture, looked to Picasso not only as an artistic innovator but as someone who branded himself with striking visual consistency, charisma, and cultural ubiquity.

Warhol saw in Picasso a model for how an artist could transcend the canvas and become a cultural icon. Picasso had made headlines not just for his paintings but for his lifestyle, his lovers, his political stances, and his sheer prolific output. Warhol absorbed this lesson and turned his own life into art — performing the role of the artist with the same calculated theatricality Picasso had mastered decades earlier.

2. Reinvention as a Lifelong Discipline

Picasso’s refusal to settle into a single style — moving from Blue Period to Rose Period, Cubism to Neoclassicism, Surrealism to Expressionism — was one of his most radical acts. For Warhol, this model of constant reinvention became a key strategy in his own artistic journey.

Though Warhol is most famous for his silkscreened celebrity portraits and consumer goods, his practice included drawing, painting, sculpture, filmmaking, publishing, performance, and installation. This polymathic range is very much in the spirit of Picasso, who once declared, “To copy others is necessary, but to copy oneself is pathetic.” Warhol internalized this ethos, producing a body of work that is stylistically diverse, yet conceptually unified by themes of fame, mortality, and replication.

3. Seriality and the Challenge to the Unique Art Object

One of Picasso’s most revolutionary ideas was to question the singularity of the artwork. He often made variations on a theme — a motif explored across a series of works, each iteration challenging the idea of the “definitive” version. This idea profoundly impacted Warhol, who pushed it further through mass production and mechanical repetition.

Warhol’s repetition of Marilyns, Maos, and Campbell’s Soup Cans was not merely an aesthetic choice, but a philosophical response to Picasso’s innovations. Warhol once remarked: “Picasso did everything — and I’m doing everything he didn’t do. I’m using industrial techniques, he used craft. I’m not painting by hand — I’m printing. But I’m still doing what he did — which is everything.” This comment reveals not rejection, but deep homage through inversion — Warhol working in Picasso’s wake, responding in kind.

4. The Aging Giant: Warhol’s Final Homage

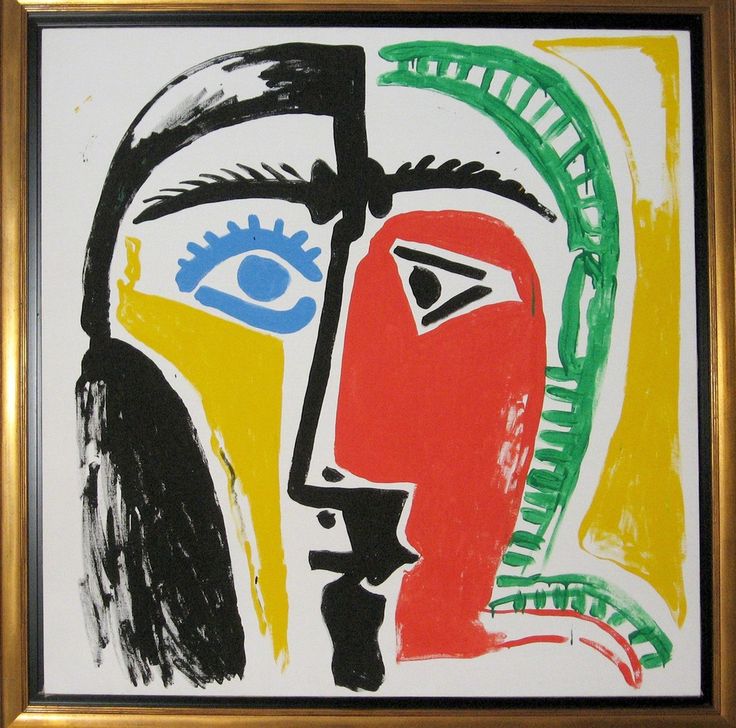

In the 1980s, as Warhol’s career entered its final phase, he openly returned to Picasso as a subject and inspiration. The series “Homage to Picasso” (1985) consists of expressive, abstracted portraits that reference Picasso’s own late style. Warhol, who had been accused of superficiality for much of his career, was in these works confronting art history directly and reverently.

These paintings are raw, direct, and gestural — a marked departure from the flat surfaces and commercial coolness of Warhol’s earlier pieces. They echo Picasso’s late portraits: distorted, mask-like, primal. In this period, Warhol seemed to be grappling not only with Picasso’s visual language, but with his legacy, measuring himself against the one artist who had cast the longest shadow over 20th-century art.

5. Persona as Medium: Picasso Walked So Warhol Could Run

Finally, both artists understood that in the 20th century, the artist’s persona was part of the work. Picasso styled himself as a passionate genius — the virile, tempestuous Spaniard with a cigarette and a mistress in every painting. Warhol, by contrast, became the passive observer — silver wig, blank expression, camera in hand — a self-effacing oracle of the media age.

Yet the lineage is clear. Warhol’s self-presentation was not born in a vacuum. He learned from Picasso that how an artist is seen is inseparable from what they make. Warhol’s public image was not just a mask, but an extension of the canvas, as calculated and curated as any of his silk screens.

Warhol’s Silkscreen of Mick Jagger in Picasso’s Collage Style

Conclusion: A Mirror in Reverse

Though Warhol’s style may appear to contrast sharply with Picasso’s, the two artists are deeply intertwined. Picasso embodied the modern artist as individual genius; Warhol redefined the postmodern artist as cultural mirror. But both reshaped the art world, both refused limitations, and both used their art to challenge the boundaries between high and low, originality and reproduction, tradition and invention.

In many ways, Warhol’s entire project can be read as a dialogue with Picasso — sometimes reverent, sometimes ironic, always engaged. If Picasso taught the world that anything could be art, Warhol showed that anyone could be an artist — and in doing so, he carried forward Picasso’s torch into a new, media-saturated age.